Imagine you are standing at the edge of a lake at dawn. The water is flat, the fog low, and every direction looks the same. You know the far shore exists, but you cannot see it. A friend hands you a battered paper compass; it carries only three numbers—ten, five, three—scratched in faded ink. Those numbers are not a map, yet they keep your oar strokes honest when the mist refuses to lift. In investing, that compass is called the 10-5-3 rule.

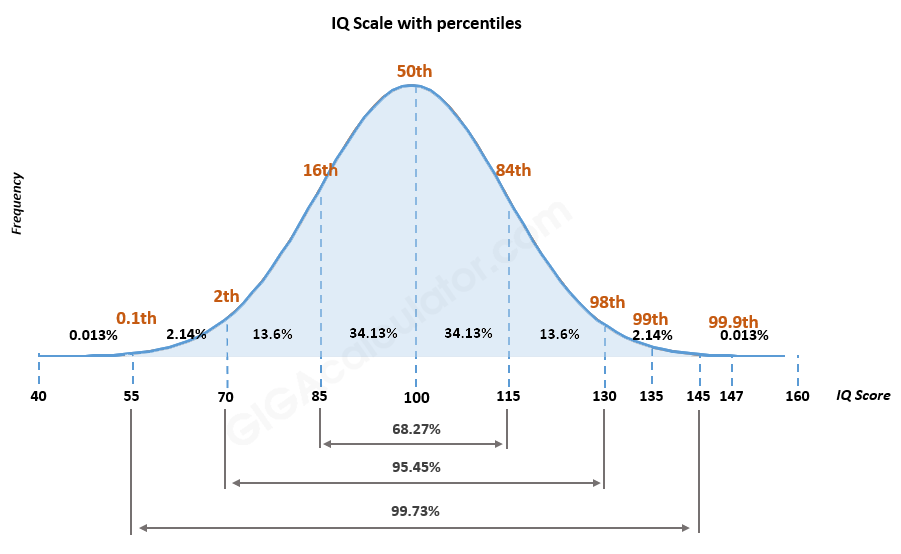

The rule whispers a simple expectation: over the long arc of years, broad baskets of equities have tended to deliver something close to ten percent a year, high-quality bonds about half that, and the safest cash-like shelters barely three. Nothing in the rule promises that next year will obey these figures; markets are weather systems, not train schedules. Instead, the numbers are averages drawn from the long sweep of American and global capital history, a shorthand for “what usually happens if you stay long enough to let the noise burn off.” They appear in James O’Donnell’s compact book The Shortest Investment Book Ever and have since been echoed by planners who need a quick way to anchor client expectations before the real tailoring begins.

Ten percent for stocks is the headline figure, and it is easy to abuse. It is seductive to imagine your money doubling every seven years, yet the rule is not a prophecy. It is a baseline for grown-up conversations: if you are thirty-five and hoping to retire at sixty, you can sketch what relentless saving plus a globally diversified equity portfolio might plausibly yield, then compare that sketch to the life you want. The moment you accept that the ten is an average across booms, crashes, wars, and technological revolutions, you stop expecting it to arrive like a paycheck and start treating it as rent you collect from capitalism itself—some months the tenant is flush, some months bankrupt, but over decades the lease holds.

Five percent for bonds is the quieter sibling, the one who keeps the flashlight in the glove compartment. Bonds do not dazzle, yet their coupons cushion the years when equities forget how to climb. Planners often pair the 10-5-3 rule with the Rule of 72: at five percent, a dollar tucked into high-grade debt doubles in roughly fourteen years, slow but reliable enough to buffer a portfolio that must also feed you when markets are on their knees. The figure is not a guarantee—today’s starting yields matter, and a bond bought at a premium may disappoint—but it is a courteous starting guess for the portion of your money assigned to steadiness rather than speed.

Three percent for cash feels almost insulting until you need it. The number acknowledges that liquidity is its own return: the price of being able to pay the hospital bill, cover the payroll, or buy more shares when everyone else is selling in panic. Inflation gnaws at that three, sometimes deeply, yet the category survives because peace of mind has value. The 10-5-3 rule quietly insists that you keep some fraction of your net worth here, not to grow but to guard the runway while the louder engines of stocks and bonds lift the rest of the plane.

Used properly, the rule is not a prescription but a conversation opener. A twenty-seven-year-old with a forty-year horizon might tilt heavily toward the ten, sprinkling just enough of the five and three to sleep at night. A sixty-two-year-old eyeing retirement in three years might reverse the weightings, locking in the five and three while letting a thinner sliver chase the ten. Neither allocation is dictated by the rule; instead, the numbers give each investor a neutral reference point against which to measure risk tolerance, cash-flow needs, and the quiet terror of outliving one’s money.

Critics fairly point out what the compass leaves out: inflation, taxes, currency swings, sequence-of-returns risk, and the emotional fragility that turns paper losses into irrevocable mistakes. The 10-5-3 forecast is blissfully blind to black-swan dives or decade-long droughts. That is why seasoned advisers treat it as a sandbox, not a statute. Run your projections, then stress-test them with lower returns, higher inflation, and earlier death. If the plan still breathes, you have built resilience into the dream.

Ultimately, the rule endures because it respects a truth too many charts obscure: most of us do not need perfect predictions; we need plausible stories simple enough to remember when fear or greed starts shouting. Ten, five, three is a lullaby for the long-term, a way to keep rowing when the fog rolls in. Hold the compass loosely, adjust for the tides of your own life, and keep paddling. The far shore is still invisible, but at least your strokes are aimed.