The winter of 2025 is teaching Europeans a lesson their grandparents hoped had been buried beneath post-war prosperity: geography is destiny, and destiny can still be cruel. As Russian glide bombs sever rail hubs in the Donbas and Belarusian armor drills within sight of the Suwałki Gap, the continent’s humanitarian mathematics has turned decisively against the people it once sheltered. After three years of absorbing more than six million Ukrainians, Poland’s shelters are full, Germany’s rent index has doubled, and France’s asylum courts face a backlog that stretches past 2027. In that suffocating context the Atlantic stops looking like an ocean and starts looking like a door left slightly ajar. Interviews conducted by the Warsaw-based Migration Policy Institute in February show a forty-percent jump in U.S. visa inquiries since October, a figure that becomes even starker when broken down by profession: trauma surgeons, cyber-security engineers, and civil-protection officers—exactly the specialists Ukraine can no longer afford to lose—now dominate the queue. Their reasoning is brutally simple: if the frontline creeps another fifty kilometers west, the European Union’s Temporary Protection Directive expires in December with no renewal in sight, and they would rather start over in Houston than in a Baltic tent city.

Washington is already adjusting the turnstiles. Although the annual refugee ceiling has been slashed to a token 7,500, the White House has quietly preserved the Uniting for Ukraine parole pipeline, which approved 186,000 newcomers between April 2022 and January 2024 and remains legally open for new applicants who can document Russian shelling within a sixty-kilometer radius of their home. Senators from Midwestern states anxious about demographic decline have begun lobbying for an expansion of the program, arguing that each displaced engineer represents not charity but a pre-screened taxpayer. Their evidence is historical: after the Soviet collapse, Eastern European immigration to the United States rose thirteen percent in any year when Brussels dithered over protection status, a pattern now repeating with digital precision. The difference is velocity; where the 1990s wave arrived by cargo ship and required years of paperwork, the current cohort books a nine-hour flight and receives work authorization on arrival, a compression that makes the exodus feel less like migration and more like evacuation.

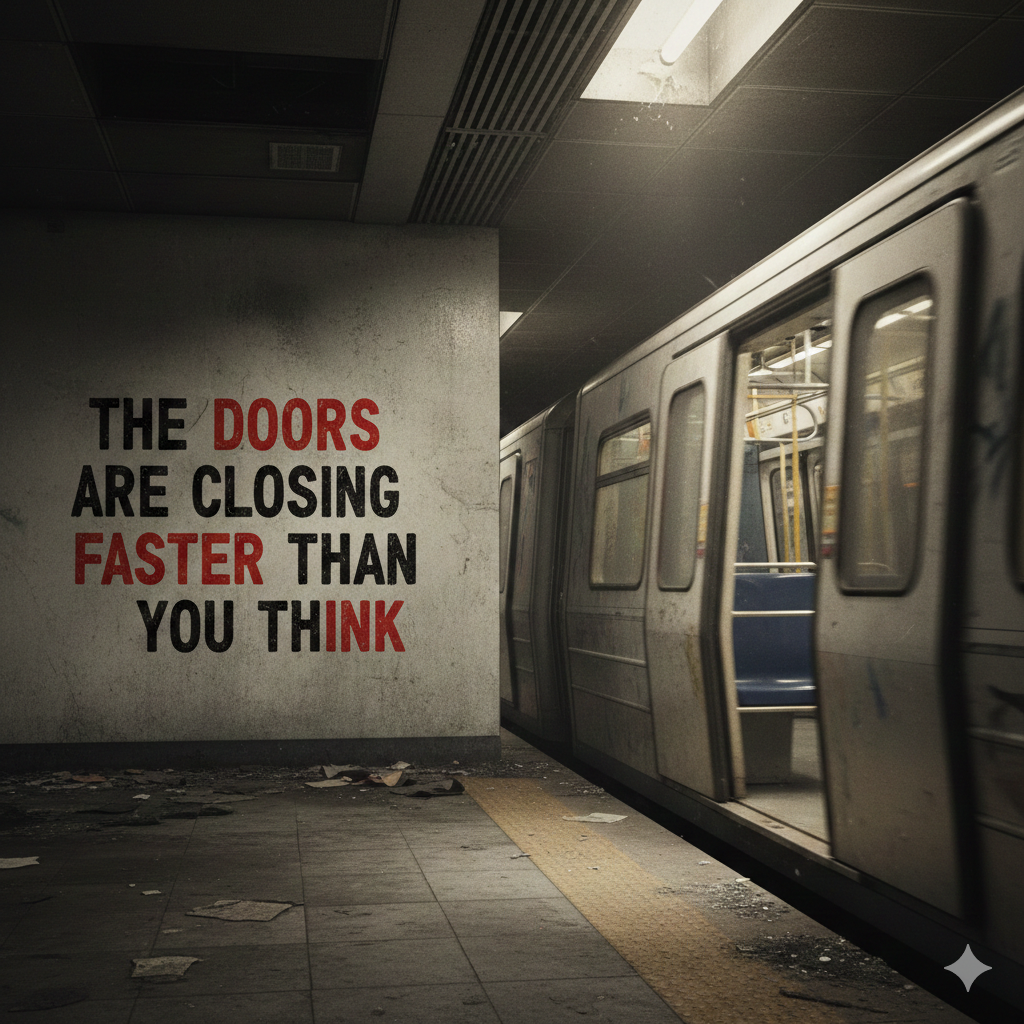

Behind the statistics lie quieter calculations being performed in kitchens from Lviv to Chișinău. Oksana, a 34-year-old pediatric intensivist who asked that her surname be withheld, spent December shuttling between a Kyiv ICU and a bomb shelter that still smells of diesel. When the hospital’s generator failed for the third time in a week, she opened her phone, uploaded scans of her medical diploma to a U.S. staffing agency, and had an employment visa within fifteen days. Her story is multiplying across professional WhatsApp groups where the discussion has shifted from “whether to leave” to “how fast the gate will close.” The gate, for now, is widening: the State Department added 1,200 new interview slots at its Frankfurt consulate in March, a number that exceeds the entire quarterly capacity for Syrian refugees during the 2016 crisis. The symbolism is impossible to miss; Europe’s stability is being stress-tested in real time, and America is positioning itself as the release valve.Critics on both continents warn that a trans-Atlantic brain drain could hollow out the very societies trying to resist Moscow’s advance. They are not wrong. The Ukrainian Ministry of Health estimates that it spent 600,000 training each of the 1,400 specialists who have already relocated under U.S. parole, a subsidy that Washington receives gratis. Yet the ministry’s own surveys show that seventy-one percent of those doctors would have left for Poland or Germany had resettlement been faster, meaning the talent was lost either way. In that light the United States is less a poacher than a destination of last resort for people who have exhausted Europe’s capacity to absorb them. The ethical dilemma is further complicated by demographics: America’s native-born population is aging at the fastest rate since the nineteenth century, and the Congressional Budget Office calculates that every Ukrainian physician who begins paying federal taxes immediately offsets 1.2 million in projected Medicare spending over a thirty-year career. What looks like charity on one shore becomes fiscal hygiene on the other.Still, the humanitarian argument remains the most politically salient. Images of Russian tanks grinding through sunflower fields have burned themselves into the American suburban imagination, and polling by Pew in January shows sixty-two percent support for “increased Ukrainian migration,” a figure that rises to seventy-eight percent when respondents are told that newcomers arrive with pre-arranged jobs. Those numbers create legislative space that did not exist during the Syrian crisis, when terrorism fears dominated the discourse. The contrast underscores a grim axiom of refugee politics: European wars feel closer to Americans than Middle Eastern ones, and whiteness—however uncomfortable the admission—still lowers the barrier to empathy. Whether that moral window stays open depends on how far the fighting spreads. If Belarusian forces open a second front in the Baltics, U.S. officials privately predict that parole applications could triple within six weeks, overwhelming the Frankfurt hub and forcing Washington to choose between bureaucratic triage and a formal refugee allotment that would require Congressional approval.

Either way, the directional current is already visible at airports from JFK to LAX, where new arrivals wearing university hoodies from Lviv Polytechnic queue for Uber pickups and speak of Ohio or Minnesota the way their grandparents once spoke of Magdeburg or Manchester. History rhymes more than it repeats, but the cadence is unmistakable: when Europe convulses, America swells with the people Europe cannot keep. The difference this time is that the voyage takes hours instead of weeks, the visas arrive by e-mail instead of steamship, and the war that drives the movement is broadcast in HD before the first refugee even boards the plane. The ocean that once made migration an epic now makes it a commute, and the continent that once exported its wars is once again exporting its futures—one trans-Atlantic ticket at a time.