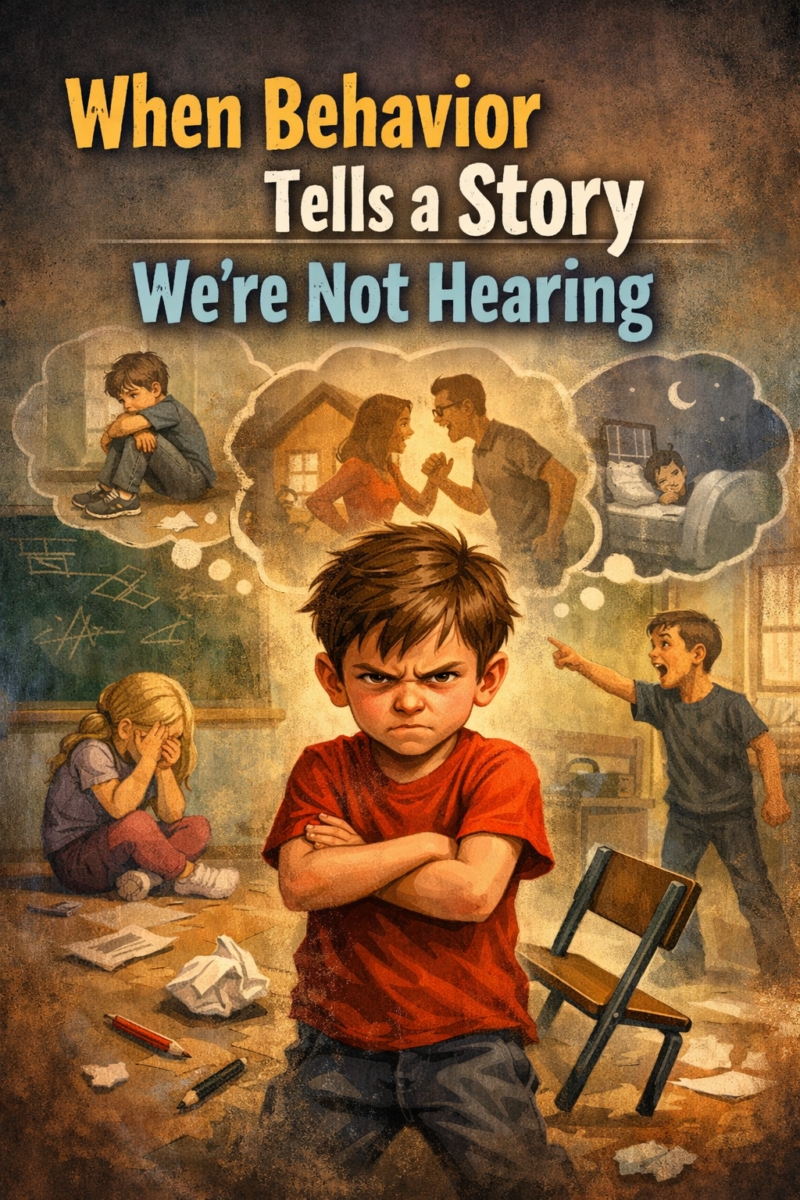

We’re quick to label them. The difficult teenager. The defiant child. The troubled youth. We see the acting out, the aggression, the withdrawal, the risky behavior, and we respond to what’s visible. But beneath the surface of these behaviors often lies a truth we’re uncomfortable confronting: many young people who are struggling have experienced abuse.

The connection between childhood trauma and behavioral problems isn’t speculation. It’s documented across decades of research in psychology, neuroscience, and social work. When a child or teenager has been physically, emotionally, or sexually abused, or has witnessed domestic violence, their brain and body are fundamentally altered by that experience. What looks like willful misbehavior is frequently a nervous system stuck in survival mode, responding to threats that may no longer be present but feel devastatingly real.

Consider the student who explodes at the smallest perceived slight. We might see defiance or anger management issues. What we might be missing is a child whose sense of safety has been so thoroughly violated that their threat detection system is permanently set to high alert. Their aggression isn’t about disrespect; it’s about protection. It’s a learned response from an environment where letting your guard down meant getting hurt.

Or think about the withdrawn teenager who seems unreachable, who skips school and avoids connection. We worry about apathy or depression, and we’re not wrong to worry. But this withdrawal might be the only way they know to cope with overwhelming shame or fear. Abuse teaches children that the world is fundamentally unsafe and that they are fundamentally unworthy. Disappearing feels safer than being seen.

The young person engaging in self-destructive behavior, using substances, or seeking out dangerous situations, is often reenacting trauma or attempting to numb unbearable emotional pain. When you’ve been taught through abuse that your body and your boundaries don’t matter, treating yourself with care can feel foreign, even impossible.

This doesn’t mean every difficult behavior stems from abuse, and it certainly doesn’t excuse harmful actions toward others. Young people are responsible for their choices, and consequences matter. But understanding the potential roots of behavior changes how we respond. Punishment alone rarely helps a traumatized child; it often reinforces their belief that they’re bad, broken, or unlovable.

What these young people need is what they often didn’t receive in the first place: safety, consistency, patience, and adults who can see past the behavior to the pain driving it. They need therapeutic support that addresses trauma, not just symptoms. They need schools and communities that recognize that connection and understanding are often more powerful than consequences.

The challenge is that trauma-driven behavior can be exhausting and frustrating to deal with. It tests the limits of parents, teachers, and counselors. It’s easier to respond with anger or give up entirely than to keep showing up with compassion for someone who seems determined to push everyone away. But that pushing away is often a test: will you abandon me like I expect, or will you prove that I’m worth staying for?

We need to shift our cultural narrative around troubled youth. Instead of asking “What’s wrong with you?” we need to ask “What happened to you?” This isn’t about excusing behavior or removing accountability. It’s about responding to young people with the curiosity and compassion that trauma-informed care requires.

The next time you encounter a young person whose behavior baffles or frustrates you, consider what might be beneath the surface. Consider that their acting out might be the only language they have to express pain they don’t have words for. Consider that behind the defiance or detachment might be a child who learned early that the world isn’t safe and that adults can’t be trusted.They’re not broken. They’re wounded. And wounds, given the right conditions, can heal.