There’s a peculiar irony in how students perceive their own struggles. Hunched over textbooks at midnight, caffeinated and anxious about exams, they dream of the day they’ll escape academia’s pressure cooker and enter the “real world.” Meanwhile, those already grinding through that real world often look back at their student years with something approaching nostalgia, remembering those all-nighters and exam crams as a kind of protected innocence.

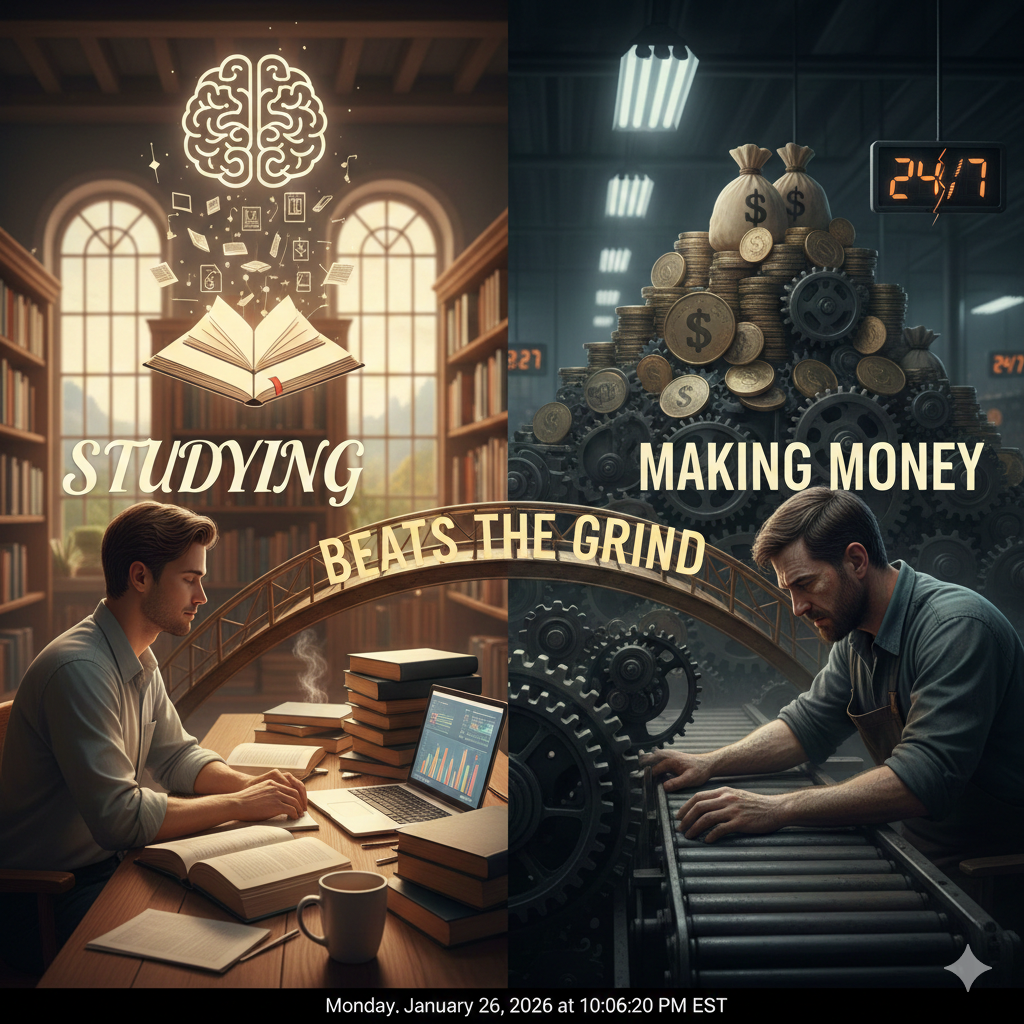

The truth that becomes clear only in hindsight is this: studying, for all its intensity, is fundamentally less strenuous and stressful than the relentless machinery of making money.

Consider the basic structure of each endeavor. When you’re studying, you’re operating within a defined system with clear boundaries. The semester has a start date and an end date. The syllabus tells you exactly what you need to know. The exam comes on a scheduled day, you take it, and then it’s over. Even the most demanding course eventually concludes. There’s a rhythm to academic life, a predictable cycle of pressure and release, challenge and respite.

Making money offers no such mercy. The work doesn’t end when you’ve proven you understand the material. There’s no final exam after which you can celebrate and move on. Instead, you wake up the next day and do it again, and the day after that, and the day after that. The bills don’t stop coming. The rent doesn’t forgive you for a bad month. Your performance isn’t measured once or twice a semester but continuously, in real time, with immediate consequences for failure.

The stakes are different too. If you fail an exam, you might retake it, possibly retake the course, or in the worst case, extend your time in school. These are setbacks, certainly, but they’re contained within an educational ecosystem designed with second chances built in. Office hours exist. Professors offer extra credit. Study groups form. The entire institution is oriented around helping you succeed, or at least giving you the tools to succeed.

When you fail at making money, people lose their homes. Families go hungry. Medical care becomes inaccessible. There’s no professor to give you partial credit for showing your work when you come up short on rent. The consequences cascade immediately into every corner of your life, and there’s no dean of students to appeal to when things go wrong.

Then there’s the matter of what’s actually being asked of you. Studying demands that you absorb information, think critically, and demonstrate understanding. These are cognitive tasks, and while they can certainly be exhausting, they’re exhausting in a way that sleep, good food, and a weekend can address. Your brain needs rest and recovery, but the wear and tear is primarily mental.

Making money, particularly for the majority of people who don’t sit in air-conditioned offices pushing papers, demands your body as well as your mind. It asks you to stand for eight-hour shifts, to lift heavy objects, to perform repetitive motions that grind down your joints over years and decades. Even in white-collar work, the stress manifests physically in high blood pressure, stress-related illnesses, and the slow accumulation of tension that settles into your shoulders and never quite leaves.

The autonomy question matters too. When you’re studying, you’re investing in yourself. You choose your major, select your courses, and pursue knowledge in areas that interest you. Even required classes serve your broader goal of education and credential-building. The entire enterprise is self-directed in a fundamental way.

Making money usually means serving someone else’s priorities. Your time belongs to your employer. Your efforts enrich someone else’s bottom line. You spend the best hours of your days doing things you wouldn’t choose to do if you didn’t need the paycheck. This fundamental lack of agency creates a particular kind of psychological strain that studying, even at its most tedious, rarely matches.

There’s also the social safety net embedded in student life. Universities provide counseling services, health centers, career guidance, libraries, and countless resources designed to support you through challenges. Your entire community consists of people going through similar experiences, creating natural solidarity and understanding. Professors, advisors, and mentors are professionally obligated to help you succeed.In the working world, you’re much more isolated. Your coworkers are often competitors for raises and promotions. Human resources serves the company, not you. If you’re struggling, there’s no institutional apparatus designed to catch you before you fall. You’re expected to handle your problems privately, on your own time, without letting them affect your productivity.

The timeline of reward differs fundamentally as well. When you study hard and do well on an exam, you see the results within days or weeks. Complete a course successfully and you earn credits that same semester. Finish your degree and you walk across a stage to receive tangible recognition of your achievement. The feedback loop is relatively tight and rewarding.

Making money offers no such immediate gratification for most people. You might work hard for years before seeing a meaningful raise. Decades might pass before you achieve financial security. The relationship between effort and reward is murky and often arbitrary, dependent on factors far beyond your control like economic conditions, industry trends, and the whims of management.

This isn’t to say that studying is easy or that students don’t face genuine hardship and stress. Academic pressure is real, and some students struggle tremendously with the demands placed on them. But there’s a crucial difference between temporary, structured difficulty with built-in support systems and the grinding, indefinite, high-stakes stress of economic survival.

The student stressed about finals will eventually take those finals, and then the semester will end. The worker stressed about making ends meet wakes up to the same problem tomorrow, and the day after, and every day for the foreseeable future, with no natural endpoint except retirement or death.

Perhaps this is why so many successful people speak fondly of their school years despite complaining about them at the time. They’ve gained the perspective that comes from experiencing both worlds. They remember studying as hard, but they know working for money is harder. One was a temporary trial in a protected environment. The other is the permanent condition of adult existence, with all the weight that entails.