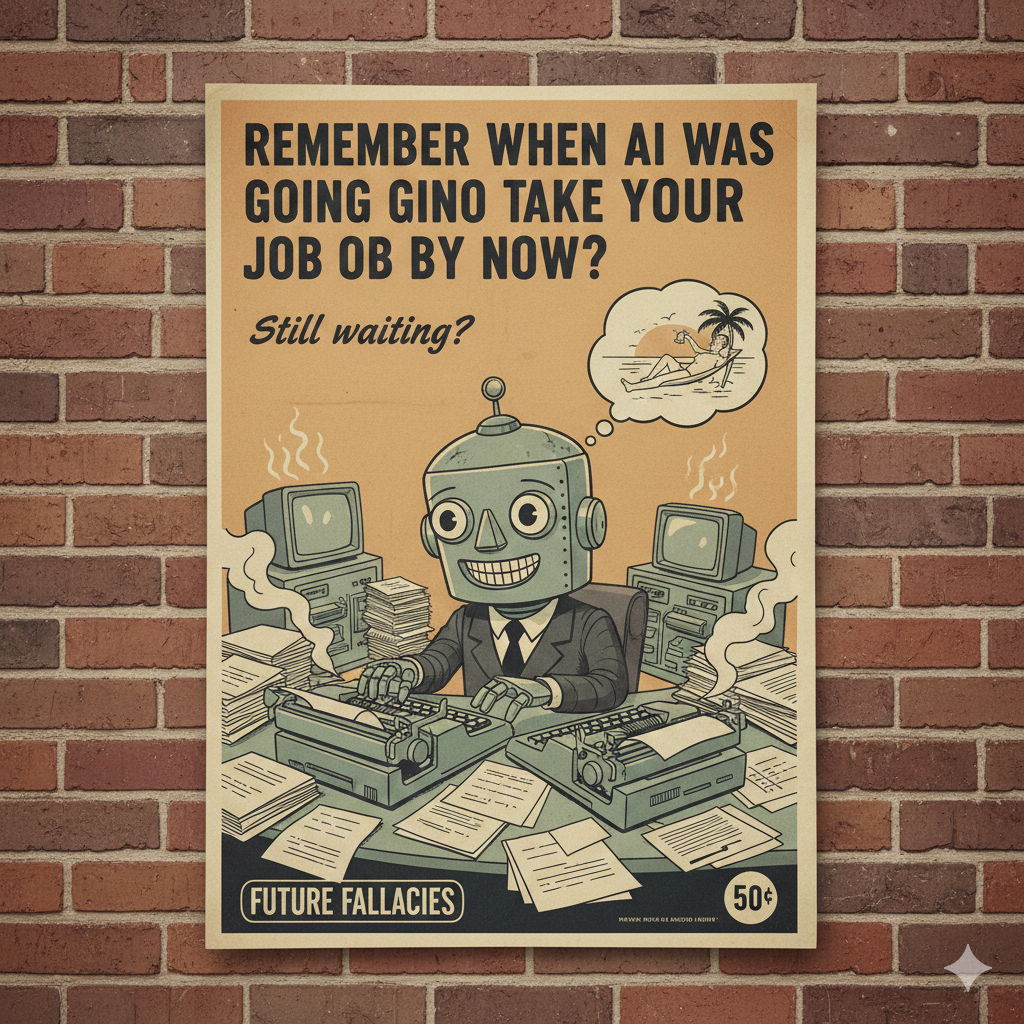

If you’re reading this in 2026, congratulations on still being employed. Or unemployed for reasons that have nothing to do with a robot stealing your desk. Either way, you’re probably not living in the dystopian wasteland of mass technological unemployment that we were all promised just a few years ago.

Cast your mind back to 2023, when every other headline screamed about how AI was coming for everyone’s livelihood. Radiologists were doomed. Programmers were finished. Writers, artists, lawyers, accountants, and customer service representatives were all supposedly on the chopping block. The robots weren’t just coming; they were practically already here, sharpening their metaphorical knives and eyeing your ergonomic office chair.

The narrative was seductive in its simplicity: AI could now do tasks that previously required human intelligence, therefore humans doing those tasks would become obsolete, therefore mass unemployment was inevitable. Some predicted fifty percent of jobs would vanish within a decade. Others were more conservative, settling on a mere twenty or thirty percent. Investment banks published breathless reports. Think pieces multiplied like rabbits. Everyone had a hot take about which profession would be first against the wall when the AI revolution came.

And yet, here we are. You probably still have a job, or know roughly the same percentage of unemployed people you did three years ago. The economy didn’t collapse under the weight of millions of newly redundant workers. Your company probably uses AI tools now, sure, but they’re more like really smart assistants than replacements for entire departments.

What happened? Did AI suddenly stop improving? Not really. The models got better, more capable, more reliable. They can do genuinely impressive things that seemed impossible just a few years ago. But it turns out that “can do impressive things” and “can replace a human worker” are separated by a chasm wider than anyone predicted.

The gap isn’t primarily technical. It’s about everything else that comes with actually getting work done in the real world. It’s about context, judgment, and the ability to navigate ambiguity. It’s about understanding what problem you’re actually trying to solve, not just the problem you think you’re solving. It’s about accountability when things go wrong, and the organizational trust required to hand over important decisions to a system that occasionally produces confident nonsense.

Most jobs, it turns out, aren’t just collections of discrete tasks that can be automated away one by one. They’re bundles of responsibilities that require synthesis, adaptation, and interaction with other humans who have their own bundles of responsibilities. The radiologist doesn’t just read scans; they consult with other doctors, understand patient histories, make judgment calls about edge cases, and provide reassurance to worried families. The programmer doesn’t just write code; they translate vague business requirements into technical specifications, argue about architecture decisions, debug mysterious issues that only appear in production, and mentor junior colleagues.

This isn’t to say AI hasn’t changed work. It absolutely has. Most knowledge workers now have access to tools that can draft documents, analyze data, generate images, and answer questions with remarkable facility. These tools have made many tasks faster and easier. Some roles have evolved significantly. But evolution isn’t extinction. Horses didn’t disappear when cars were invented; they just stopped being the primary mode of transportation and found different niches.

The economic story is messier too. Even when automation can technically replace workers, companies don’t always rush to do it. There are implementation costs, retraining costs, and risks if the new system fails. There’s the small matter of customers who actually prefer interacting with humans. And there’s the inconvenient fact that while AI can reduce the time needed for certain tasks, demand for those tasks often expands to fill the gap. Lawyers use AI to review documents faster, which means they can take on more cases, not that they fire half their staff.

Perhaps the most important lesson from these past few years is about the difference between technological possibility and economic inevitability. Just because something can be automated doesn’t mean it will be, and even when it is, the effects ripple through the economy in unpredictable ways. Technology doesn’t just destroy jobs; it changes them, creates new ones, and redistributes economic value in ways that take years or decades to fully manifest.This doesn’t mean workers can relax completely. AI will continue improving, and its impact on employment will continue growing. Some jobs really will disappear or transform beyond recognition. The factory worker replaced by robots was told not to worry too many times for us to be cavalier about it now. But the simplistic narrative of imminent mass replacement turned out to be, well, simplistic.

So if you’re still doing essentially the same job you were doing in 2023, perhaps with some new AI tools in your workflow, you’re not an exception. You’re the norm. The robot apocalypse was delayed not by some technical failure, but by the stubborn complexity of human work itself. Your job, with all its weird quirks and context-dependent decisions and interpersonal dynamics, turned out to be harder to replace than a PowerPoint presentation suggested.

The future will bring more change, certainly. But maybe we can approach it with slightly less hysteria and slightly more attention to how technology and human work have actually coexisted throughout history: messily, gradually, and with far more continuity than the headlines would have you believe.