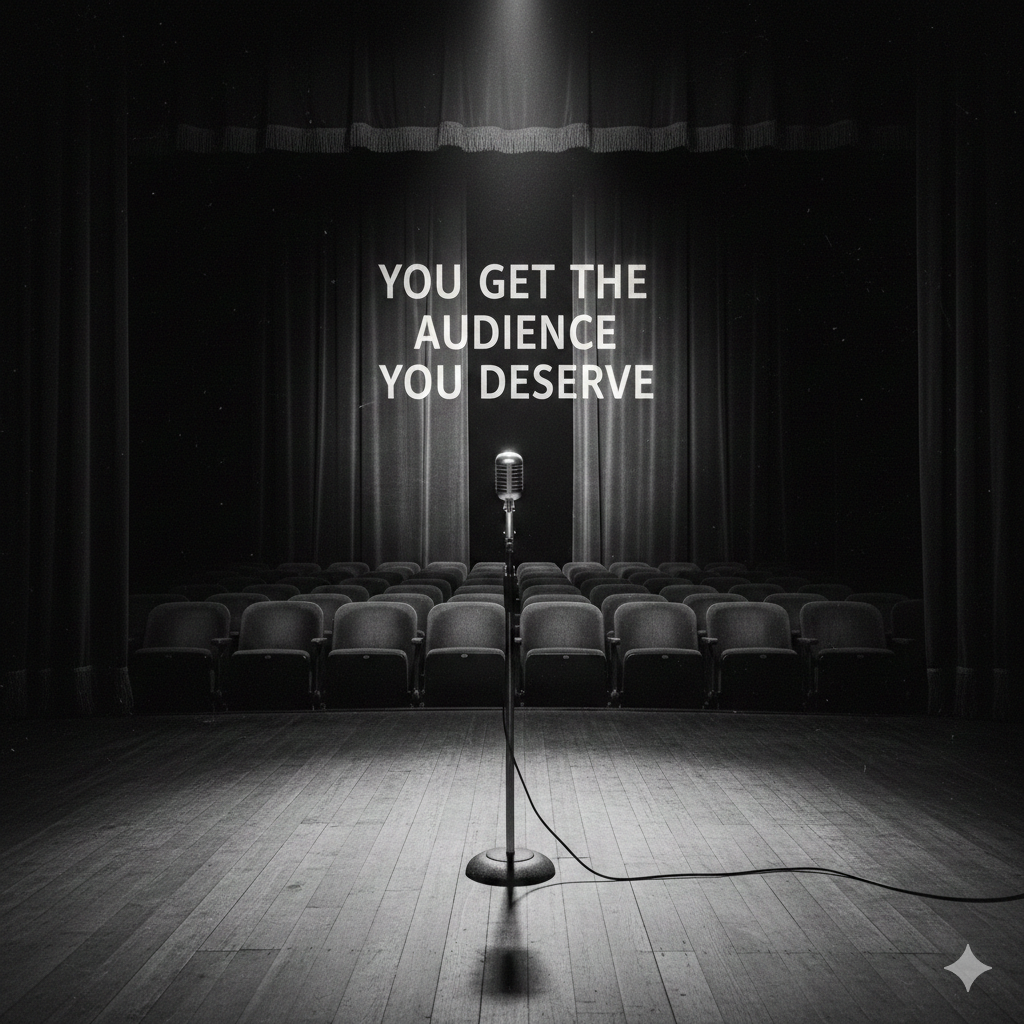

Standing in front of a crowd and realizing you do not like the people looking back at you is a lonely experience. It isn’t the anxiety of performance, nor the fear of judgment. It’s something quieter and more insidious: the awareness that you have built something you don’t want to inhabit. This is the secret shame of many content creators who discover they’ve built an audience they can’t stand.

The uncomfortable truth is that your audience is never an accident. They are the cumulative result of every choice you have made, every post you published, and every boundary you have failed to set. If you find yourself resenting the people who consume your work, you are not a victim of bad luck or internet culture. You are experiencing the consequences of your creative decisions.

Consider the creator who begins with true intentions, sharing essays about literature and slowly finds their comment section filled with arguments about canonical merit. Or the fitness influencer who wanted to encourage sustainable health but attracted an audience obsessed with extreme transformation and quick fixes. Or the humorist whose satirical edge drew in readers who missed the irony and now demand increasingly cynical, mean-spirited content. In each case, the creator looks at their analytics with a kind of nausea, watching engagement climb while satisfaction plummets. They have succeeded by every metric except the one that matters: they don’t want to spend time with the community they have built.

This dynamic reveals something fundamental about the relationship between creator and audience. Your readership is not merely a demographic to be analyzed or a market to be exploited. They are a reflection of your values as expressed through your work. When you prioritize growth over integrity, when you chase trends that do not align with your genuine interests, you are engaging in a form of self-betrayal that eventually becomes impossible to ignore. The audience you attract under these conditions is not wrong for being who they are. They are simply responding to signals you sent, often signals you did not realize you were transmitting.

The tragedy is that this resentment often curdles into contempt, and that contempt leaks into your work. The creator begins to perform disdain for their own audience, writing with a sneer, creating content that mocks the very people they rely upon for survival. This is a death spiral, creatively and ethically. It produces hollow work and miserable days. No amount of money compensates for the exhaustion of performing for people you secretly despise, especially when you understand that you are the architect of your own dissatisfaction.

There is no solution here that does not involve accountability. You cannot swap out your audience like a defective product. You cannot issue a recall on the community you have built. The only path forward is through the uncomfortable work of examining how you arrived here and what you are willing to change. This might mean losing followers. It might mean slower growth. It might mean a period of confusion as you recalibrate your voice and your values. But the alternative is worse: continuing to produce work that drains you, serving an audience that diminishes you, all while pretending this is simply the cost of doing business.

The relationship between creator and audience should be one of mutual respect. When it works, there is a genuine pleasure in the exchange, a sense that you are speaking to people who understand what you are trying to do and who want you to succeed at it. These are the audiences that sustain careers over decades, that forgive missteps, that grow with you as you evolve. They are not built through manipulation or algorithmic optimization. They are built through consistency of purpose, through the courage to be specific rather than generic, through the willingness to say things that attract the right people even if it means repelling the wrong ones.

If you don’t like your audience, you have failed as an artist. You have failed to be honest about what you care about and what you want to contribute. The good news is that this failure is reversible, though never without cost. You can begin again. You can write to the person you wish were listening. You can trust that clarity attracts and vagueness accumulates, and that the more specific you are about your perspective, the more likely you are to find readers who genuinely share it.

Your audience is not a force of nature. They are not a random sampling of humanity foisted upon you fate. They are your collaborators, your partners in the strange intimacy of public creation. Treat them as such from the beginning, or be prepared to face the alienation that comes from discovering you have built a home you do not want to live in. The empty room is not the problem. The problem is filling it with people you never wanted to invite inside.