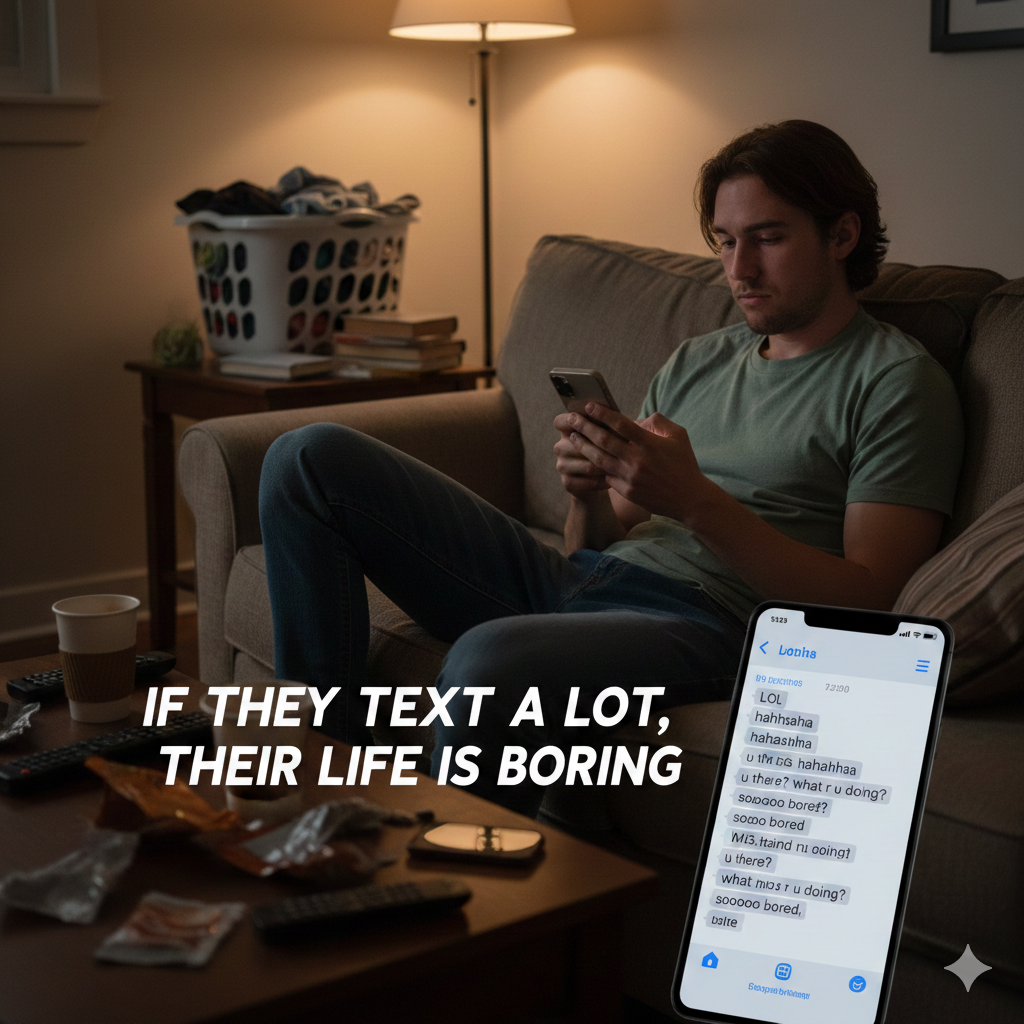

There is a peculiar modern phenomenon that plays out in restaurants, on public transport, and in living rooms around the world. It involves the reflexive glance at a blank screen, the phantom vibration in a pocket, and the immediate, almost compulsive, reaching for a device the moment a conversation lulls or an elevator door closes. We have become a species that abhors the quiet boredom of an empty moment, filling every potential pocket of silence with the digital equivalent of static. This behavior, so ubiquitous it feels almost invisible, might actually be telling a subtle story about the life of the person holding the phone.

The argument can be made that a person who is perpetually contactable, whose thumb hovers eternally over the send button, whose attention is split between the physical world and the glowing rectangle in their hand, may be signaling something profound about the world they are trying to escape. It suggests that the reality unfolding around them, their “real life,” is simply not engaging enough to hold their focus. If you are at a concert, truly immersed in the music, the last thing you want to do is pull out your phone to text someone about it. If you are in the middle of a captivating conversation with a friend, the idea of interrupting it to check a notification feels like a minor sacrilege.

The phone, in this context, becomes a barometer of interest. When the movie is dull, you check your messages. When the party conversation turns to a topic that doesn’t involve you, you scroll through a social media feed. The device is the refuge we retreat to when the present moment fails to deliver. Therefore, the person who is always, instantly available, who responds to texts within seconds no matter the time of day, is often a person whose present moment is consistently failing them. Their virtual world has become more compelling than their physical one, not because the virtual is so fantastic, but because the physical has become so hollow.

This is not a judgment on character, but an observation on circumstance. A life packed with spontaneous adventure, deep, in-person connections, and challenging, absorbing tasks leaves very little room for the dead air that our phones are designed to fill. When you are hiking a trail, building a piece of furniture, or locked in a playful debate with a loved one, the phone becomes a forgotten object, an afterthought left in a coat pocket. Its pull weakens in direct proportion to the strength of your engagement with the world. The constant, pinging companion is, ironically, a sign of loneliness.

Consider the alternative. The person who takes hours to reply, who sometimes misses a text entirely, who is frustratingly difficult to get a hold of. They are not necessarily being rude. They are simply, and profoundly, elsewhere. They are lost in a book, immersed in a project, or deeply present with another human being. Their unavailability is not a rejection of you, but an embrace of their own reality. They have built or found a life that demands their presence, not just their attention. They have discovered that the most interesting thing to do with a phone is often to put it down.

Ultimately, our devices are portals to everywhere, which can make the simple act of being somewhere feel insufficient. The most reachable person is often the one running from the quiet whisper of their own unoccupied mind, seeking validation or distraction in a stream of digital noise. The person living a truly interesting life has little need to peek into everyone else’s. They are too busy living their own, one un-reachable, fully-engaged moment at a time.