We are, all of us, curators of our own past. We walk the hallways of memory, selecting moments to display, to polish, to revisit in the quiet hours. This is a natural, human process. But there is a danger, subtle and corrosive, in becoming the sole visitor to a single, unchanging exhibit. When we fixate on particular points in our personal history—a painful regret, a searing injustice, a golden moment of triumph that has long since faded—we begin a quiet work of distortion. We don’t just remember these moments; we unconsciously build our entire present mind around them, warping its architecture until the view is forever skewed.

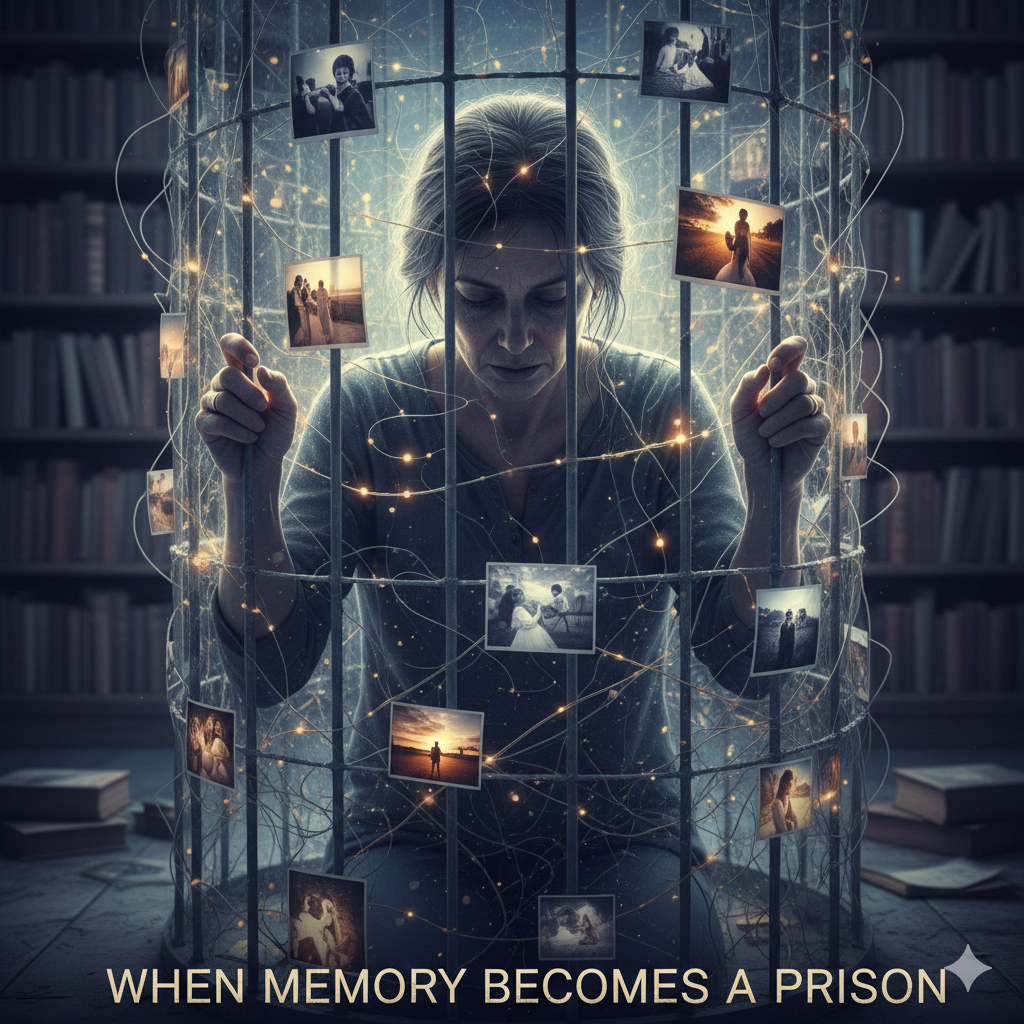

This focus acts not as a window, but as a lens, bending the light of everything else we see. That one failure becomes the defining proof of our inadequacy, casting long shadows over subsequent successes, which now feel like flukes. That past betrayal becomes the filter through which we view all new relationships, staining gestures of kindness with the hue of suspicion. We mistake the fragment for the whole story, the single chapter for the entire book. The vibrant, complex, and ever-evolving person you are today becomes a prisoner to a ghost, forced to perform a play scripted by a self you no longer inhabit.

The mind, in its relentless search for patterns, uses these focal points as anchors. It begins to organize new information not as it is, but as it relates to that old wound or that old glory. A simple setback at work is no longer just a setback; it is a confirmation of the narrative of “I always fail.” A compliment is dismissed, not heard on its own merit, because it contradicts the older, louder story of being unworthy. This is the distortion: the past ceases to be a reference point and becomes a ruling doctrine. It flattens the rich, three-dimensional landscape of the present into a two-dimensional silhouette of what has been.

Worse, this obsession fossilizes the self. Human beings are rivers, not monuments. We are meant to flow, to change course, to be shaped by new banks and weather. But by tethering our identity so tightly to a fixed point back on the shore, we refuse the current. We insist that the person who was hurt, or who was foolish, or who was brilliant, is the only person we can ever be. We deny ourselves the right to grow, to forgive, to be surprised by our own resilience. The mind becomes a room echoing with a single conversation on repeat, drowning out the symphony of possibilities happening right outside the door.

To free the mind from this distortion is not to erase the past or to practice a shallow positivity. It is, instead, to change your relationship with it. It is to gently escort that painful memory from the center of the gallery and place it back on the wall among all the others—the joys, the mundane days, the quiet learnings, the loves. It is to see it as a part of your history, but not its curator. It is to grant yourself the profound authority to narrate your own life from the vantage point of the present, with all its hard-won wisdom, not from the trapped perspective of a moment frozen in time.

The past is a place of reference, not a place of residence. Your mind is a vast and dynamic landscape, capable of holding the full spectrum of your experience without being held hostage by any single part of it. When you stop staring at the same few pictures, you can finally look out the window. And you might just see that the world outside—and the person observing it—is far wider, brighter, and more alive than you remembered.