We’re taught from childhood that honest communication can resolve most conflicts. Sit down, talk it through, find common ground. This advice works well in the overwhelming majority of human interactions, but it crashes spectacularly when applied to individuals with antisocial personality disorder, commonly known as sociopaths.

The fundamental problem is asymmetry. Good faith conversation requires both parties to share certain basic commitments: honesty, mutual respect, and a genuine interest in understanding the other person’s perspective. When you enter a conversation assuming these shared values, you’re operating with one hand tied behind your back if the other person doesn’t share them.

Sociopaths, by clinical definition, lack the capacity for genuine empathy and operate primarily through manipulation. They don’t experience the emotional feedback loop that makes most people feel uncomfortable when lying or exploiting others. Where you might feel guilt or shame for misleading someone, they feel nothing, or perhaps even satisfaction at successfully deceiving you. This isn’t a moral judgment so much as a description of how their psychology differs fundamentally from the neurotypical experience.

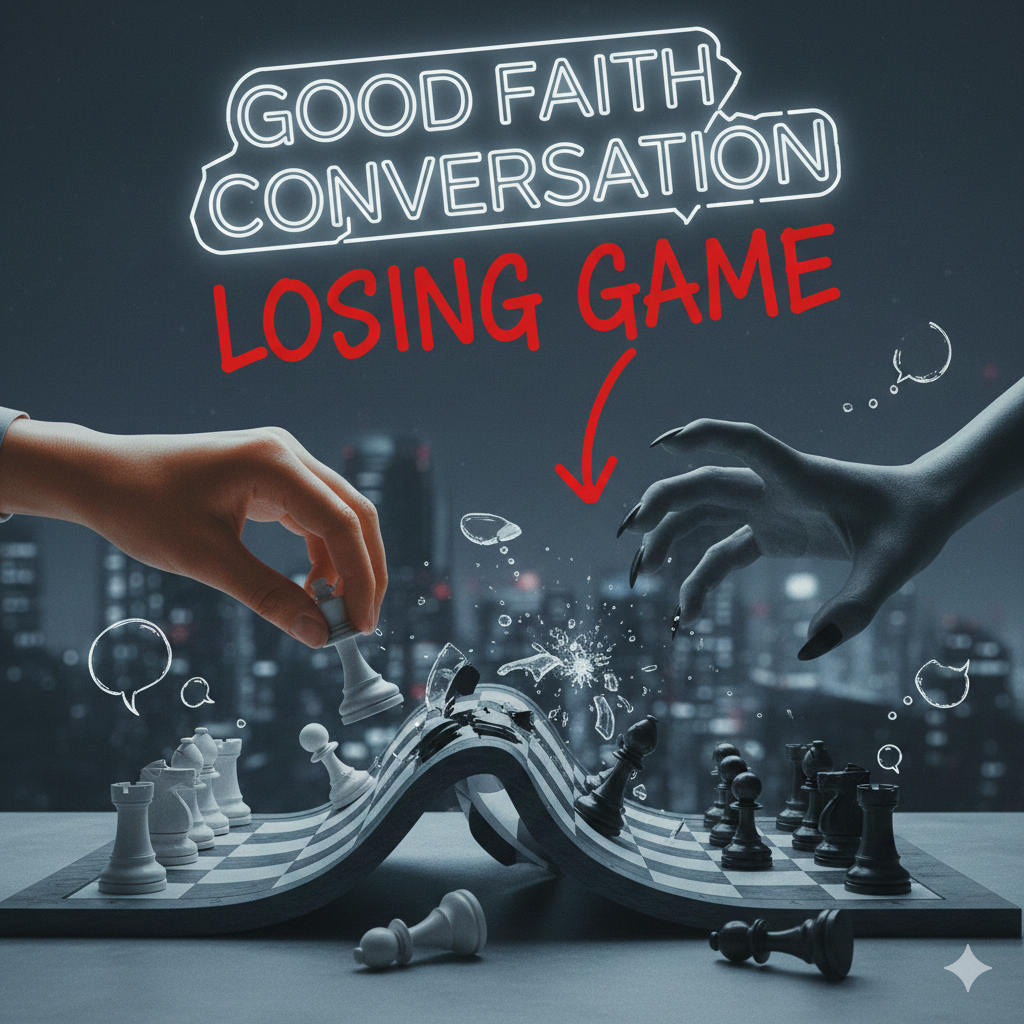

When you attempt good faith dialogue with someone operating this way, you’re essentially playing chess while they’re playing poker with a marked deck. You’re trying to find truth and mutual understanding. They’re trying to win, where winning means getting what they want from you while giving up as little as possible. Your honesty becomes a vulnerability they can exploit. Your willingness to see their perspective becomes an opening for manipulation.

Consider what happens in a typical good faith conversation. You share your genuine thoughts and feelings. You admit uncertainty where you feel it. You acknowledge the validity of points the other person makes. You’re willing to be persuaded if they present compelling arguments. All of this is healthy and productive when both people are engaging sincerely.

But a sociopath will catalog your admissions of uncertainty as weaknesses to exploit later. They’ll note which emotional appeals affect you and deploy them strategically. They’ll agree with you when it’s convenient and flatly contradict themselves later without a hint of self-consciousness. They’ll share fabricated vulnerabilities to create false intimacy, making you feel like you’re finally getting through to them, when really they’re just giving you what you want to hear.

The conversation itself becomes a tool of manipulation. You leave thinking you’ve made progress, that you’ve established understanding, that things will improve. Meanwhile, they’ve simply identified which buttons to push next time they need something from you. Your good faith effort has handed them a more detailed map of your psychology.This doesn’t mean sociopaths are masterminds who never make mistakes or that they’re inhuman monsters. They’re people with a specific psychological condition that makes certain kinds of genuine connection functionally impossible for them. Many go through life causing minimal harm, learning to navigate social expectations through calculation rather than feeling. But when they do choose to manipulate, your good faith engagement won’t reach them because the psychological machinery that good faith conversation relies on simply isn’t there.

The appropriate response isn’t to try harder to reach them through honest dialogue. It’s to recognize that certain conversations are structurally impossible and to adjust your behavior accordingly. This means establishing firm boundaries, refusing to be drawn into extended justifications or explanations, and accepting that you cannot reason someone into caring about your wellbeing if they’re constitutionally incapable of that kind of concern.

It’s a hard lesson because it cuts against everything we believe about human connection and redemption. We want to believe that everyone can be reached, that the right words said with enough sincerity can break through any barrier. But some barriers are neurological, not emotional or intellectual. You wouldn’t expect a colorblind person to see red no matter how eloquently you described it. Similarly, you can’t expect someone without empathy to suddenly develop it through conversation.

The kindest thing you can do, both for yourself and paradoxically for them, is to stop pretending that good faith dialogue is possible where it isn’t. Set clear boundaries, enforce consequences, and don’t waste your emotional energy trying to forge a connection that cannot exist in the form you’re imagining. Save your good faith efforts for the vast majority of people who can actually reciprocate them.